Talk about a debut: in 1969, Fassbinder made an astounding four feature-length films -- and that, amazingly, wasn't all he did; he acted in a few others and also had his theatre-work to keep up -- of which I have now seen the first three. None of them are what I would call great, but they aren't without talent, style or intelligence either. They're closer to what I would call apprentice work: cheaply-made, frankly and somewhat ironically derivative of Hollywood crime films of the 1940s, and deeply influenced by the French New Wave.

A review of the first one is below; I'm still trying to work out my thoughts on the other two.

Love is Colder Than Death is dedicated to New Wave icons Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, and Jean-Marie Straub and "Linio Et Cuncho," reportedly the misspelling of a couple of characters in Damiano Damiani's 1967 spaghetti Western Quien sabe? (U.S. title: A Bullet for the General.) Lest we miss any of this, there's even an ill-fated character named Erika Rohmer.

None of the above, however, casts quite so large a shadow as Jean-Luc Godard, who seems to have been something of a model to Fassbinder in his speed, feverish enthusiasm, and downright bravado in pushing the limits of the audience's patience. This is a film made by someone burning to do it, who has a head full of ideas based on years of avid viewing. Like Godard's Breathless and Band of Outsiders, Fassbinder's debut is a cool, stylishly directed postmodern outlaw romance, an act of criticism whose cheapness is as much a part of its aesthetic as it is its charm, because Fassbinder's visual sense more than compensates for what, at this stage, he lacks as a writer and dramatist.

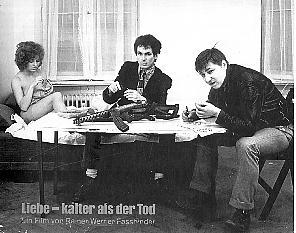

Fassbinder plays a thug named Franz, who is beaten into becoming a member of a mob syndicate, where he meets up with Bruno (Ulli Lommel). After some time apart, Bruno comes calling on Franz, whom we now discover is a low-level pimp with a hooker girlfriend, Joanna (the striking Hanna Schygulla, who became Fassbinder's leading lady). Franz is also laying low from someone who mistakenly thinks he was involved in a murder. Thus begins a kind of loose, aimless menage a trois in which this trio -- very much like Godard's band of outsiders -- go on a robbery spree that ultimately involves some killings, starting with Bruno's sudden elimination of Franz's nemesis. The others involve people who simply get in the way, like the poor store clerk Erika, and one of Joanna'a hapless johns, who is beaten and killed mainly for kicks. Bruno also gets it in the end, as we discover (again, for reasons that are somewhat underwritten in the script) that he has been ordered to kill Joanna, apparently to get at Franz, except that Bruno gets knocked off first. Franz and Joanna escape to nowhere; the last we see of them they are driving down a road, when Franz rather uselessly calls Joanna a whore.

It's not much of a story -- a love triangle between thinly-conceived characters, wrapped in a threadbare crime story, performed by non-professionals whose acting isn't so much bad as it is non-existent -- but it's fascinating to watch, for a couple of reasons. One is that it's deliberately artificial and theatrical, a factor I suspect was driven by the budget. Fassbinder had no more time or money for good actors than he did for staging convincing fight scenes or adequately synchronizing gunshots and falling bodies, but he shaped the story not to conceal these limits as to acknowledge them, thereby launching a sort of defensive first strike against incompetence.

The word deliberate kept coming to mind as I watched it, because everything about it -- particularly everything about it that seems conventionally wrong or ill-conceived -- also seems perfectly calculated, not so much to get you in the mood as to counteract whatever mood you might be hoping to feel. It's not a suspenseful slice of film noir so much as it is a deeply ambient one about losers on the skids. The music gets overwhelmingly dramatic when your instincts tell you it should be light or alluring or foreboding, and Fassbinder frequently interrupts the action with static but intriguingly composed shots, or an unendurably long freeze-frame close-up scored to lush music, or long meandering takes of the principals walking or driving or shopping or laying around or smoking (like chimneys). Fassbinder approaches every scene with a sense of adventure, and even when it drags the film never loses its visual momentum. The high-contrast black and white cinematography has a severe, chilly look to it that underscores the title. The whites are blinding, and the blacks are grainy and grim, creating an overwhelming sense of emptiness, as if these characters live in some sort of emotional Antarctica.

No comments:

Post a Comment